- Introduction

- Initial Observations

- Reviewing Assembly and IDA Decompilation

- Extracting Files

- Reading Textures

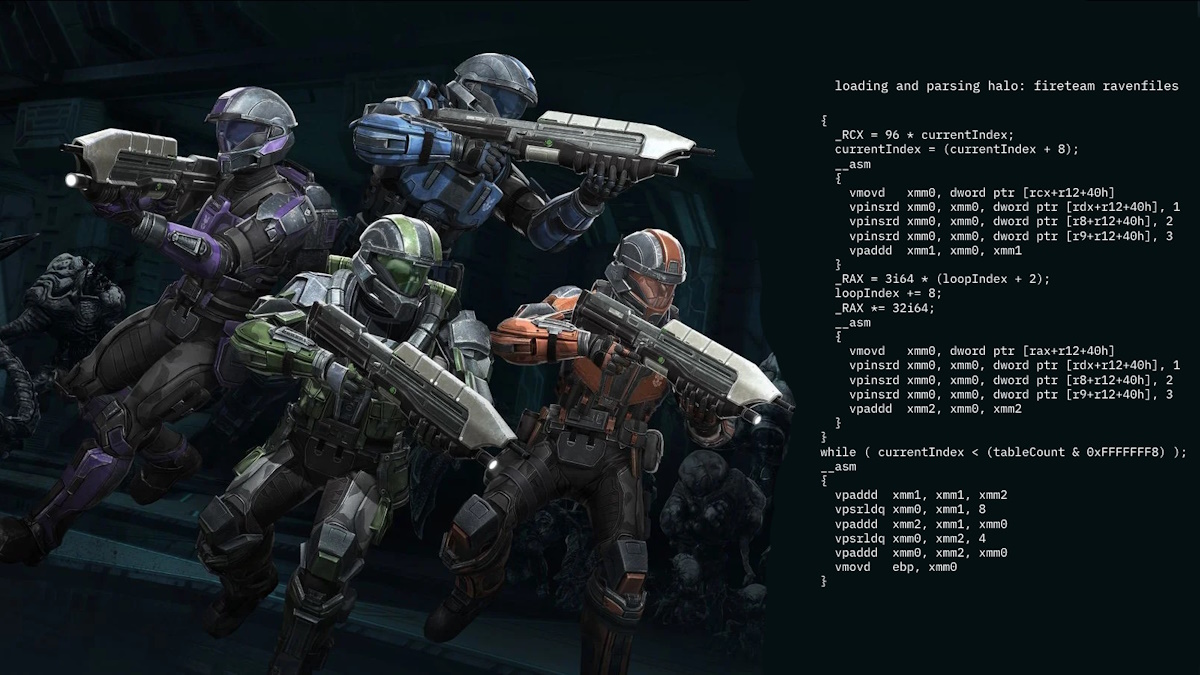

Halo: Fireteam Raven ODSTs next to IDA Decompilation Output of the game.

Halo: Fireteam Raven ODSTs next to IDA Decompilation Output of the game.

Introduction

A while back, I received some files that were presumably from a Halo: Fireteam Raven arcade machine. Alongside a windows executable, there were also some non-encrypted files with the extension of “.g7”. After looking through some of the strings in the executable, I found out that this was an in-house game engine made by Play Mechanix, a subsidiary of Raw Thrills. There was no documentation available for any of the formats, no open-source tools or even any mention of the engine on arcade forums, which simply left me with the executable and the .g7 files.

Initial Observations

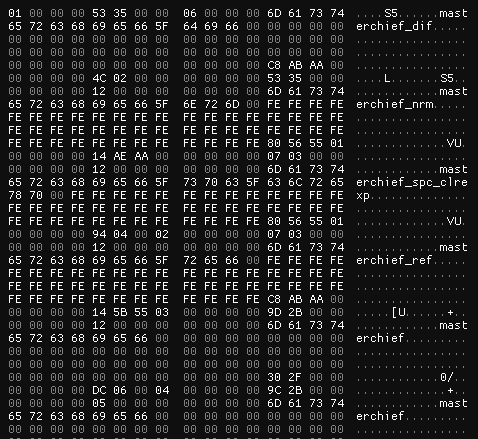

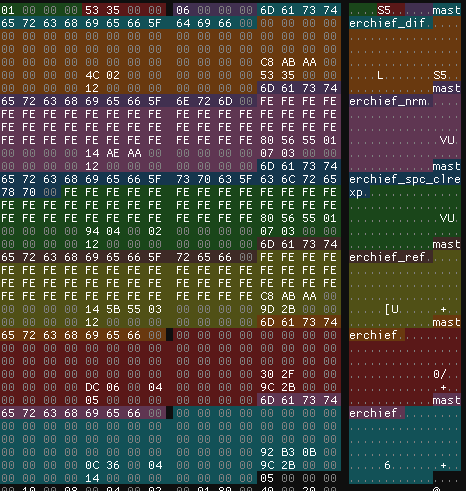

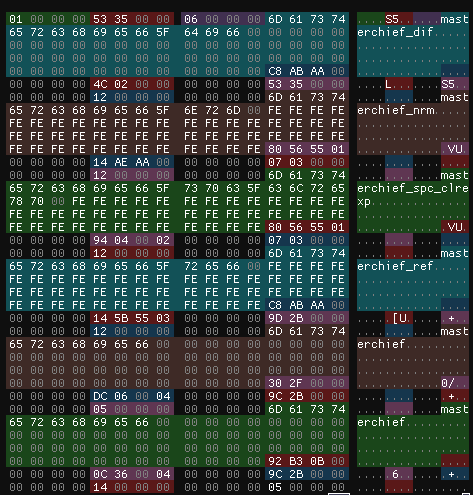

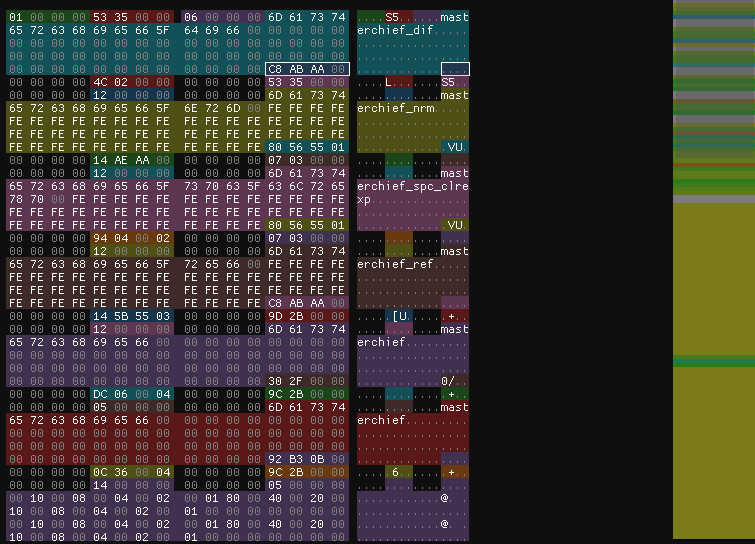

When opened in a hex editor, the G7 files looked to contain some sort of list of strings and some data after. The initial 4 bytes were always set to 1, which I presumed was some sort of flag or magic. A “block” of this data seemed to be 96 bytes, in an array. I looked for the block count, which was conveniently before the list began, at 0x08.

After this though, I was essentially stuck. My general structure for the file header was quite simple and lacked any naming.

- 0x00: int32 magic

- 0x04: int32 unknown

- 0x08: int32 blockCount

- char blocks[blockCount*96]

Reviewing Assembly and IDA Decompilation

Having reviewed some of the source files for the game and finding references to a G7_LOAD function, I decided to take a shot in decompiling the game in IDA Pro. The header files of the game seemed to indicate that it was written in C, much more easy to reverse engineer than the “TEB hell” which I call compiled C++ code. I quickly searched for the fopen function, which would trace to the function that loads the .g7 files.

I found the function rather quickly due to the game passing %s.g7 to the open function, which would be the file we are trying to reverse. The function, located at game.exe+4D4FB0, followed the same structure as my previous findings for the header. 12 bytes were read and stored in a Buffer, with the last 4 (being the block count) stored as a variable. I quickly renamed the variable to contentTableCount, which I found was the internal name for what we previously called the block table. Pretty close, huh?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

v13 = fopen(FileName, "rb"); // open file

Stream = v13; // assign local var to file pointer

v14 = v13;

if ( !v13 ) // exit if file can't open

return -1;

if ( !fread(Buffer, 12, 1, v13) ) // read 12 bytes (header)

return -2; // return -2 if file can't be read

// Buffer = rsp+70

// tableCount = rsp+78h (read 8 bytes in buffer)

v72 = sub_4291B0(96 * tableCount); // allocate memory for 96 bytes in buffer

_R12 = v72; // set R12 register to memory adress

// we can now offset the register for the table

if ( !v72 ) // if memory doesn't exist

return -1;

memset(v72, 0, 96 * tableCount); // null out buffer

if ( !fread(v72, 96 * tableCount, 1, v14) )

{

*v8 = 5;

logToGame("Couldn't read table of contents for %s", Destination);

return -1;

}

After this part of the function, I was faced with a much larger problem: SIMD that IDA could not decompile.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

{

_RCX = 96 * currentIndex;

currentIndex = (currentIndex + 8);

__asm

{

vmovd xmm0, dword ptr [rcx+r12+40h]

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [rdx+r12+40h], 1

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [r8+r12+40h], 2

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [r9+r12+40h], 3

vpaddd xmm1, xmm0, xmm1

}

_RAX = 3 * (loopIndex + 2);

loopIndex += 8;

_RAX *= 32;

__asm

{

vmovd xmm0, dword ptr [rax+r12+40h]

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [rdx+r12+40h], 1

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [r8+r12+40h], 2

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [r9+r12+40h], 3

vpaddd xmm2, xmm0, xmm2

}

}

while ( currentIndex < (tableCount & 0xFFFFFFF8) );

__asm

{

vpaddd xmm1, xmm1, xmm2

vpsrldq xmm0, xmm1, 8

vpaddd xmm2, xmm1, xmm0

vpsrldq xmm0, xmm2, 4

vpaddd xmm0, xmm2, xmm0

vmovd ebp, xmm0

}

I had never seen intrinsincs in a decompilation before, so I searched for these specific instructions. It turns out that this is simply a compiler optimized version of SSE2’s _mm_set_epi32! The function itself reads 4 32-bit integer values from a 128-bit integer. Besides this, 0x40 offsets for the registers indicated that the strings in the block have a fixed size of 64 bytes, leaving 32 bytes to read.

The _mm_set_epi32 intrinsic itself only reads 16 bytes of data, so where’s the other 16 bytes? The answer is that I don’t know. I might not be reading something properly, but it seems to simply skip over 4 bytes after each vector int is read. This might be to account for AVX2’s 32 byte intrinsics, though I’m not sure. If you have any insight into this, please let me know on Twitter.

What we now have though is a complete understanding of the header and content table entries, or at least the data types for them. I quickly moved this over to ImHex, where we started to see a proper picture of the file. After each entry, 4 bytes were skipped, nulled on the file.

Extracting Files

Now that we have our types set up, it’s time to review their values. The first integer value seemed to be random, with values like 11185096 and 22369920. What I did notice was that some of the entries in the content table shared values, but I left it unnamed for the time. The second integer however was much more interesting. Here was a set of values:

- 588

- 11185684

- 33555604

- 55925524

It seemed to be constantly increasing! Constantly increasing by the first integer value we found in fact! This pretty much confirms that the first integer value was a size and the second was offset. We can now read each file entry in the file.

Before that though, I also looked at the two integer values we had left. The third integer value is a complete mystery and seems to be random, I have yet to figure it out. I believe that it might be some sort of file ID for global loading, though I have no concrete proof on that.

The fourth value is much more interesting though. Each file had its value set to small integers like 20, 3, 18. After checking their file names, it became apparent that this was some sort of assetType variable. Each value would require different processing, such as with textures and models. Here’s all that I managed to put together:

- 20: models

- 18: bitmaps

- 5: rig

- 3: camera

- 4: cinematic camera?

Reading Textures

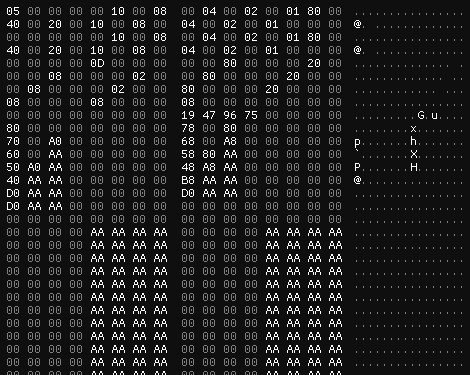

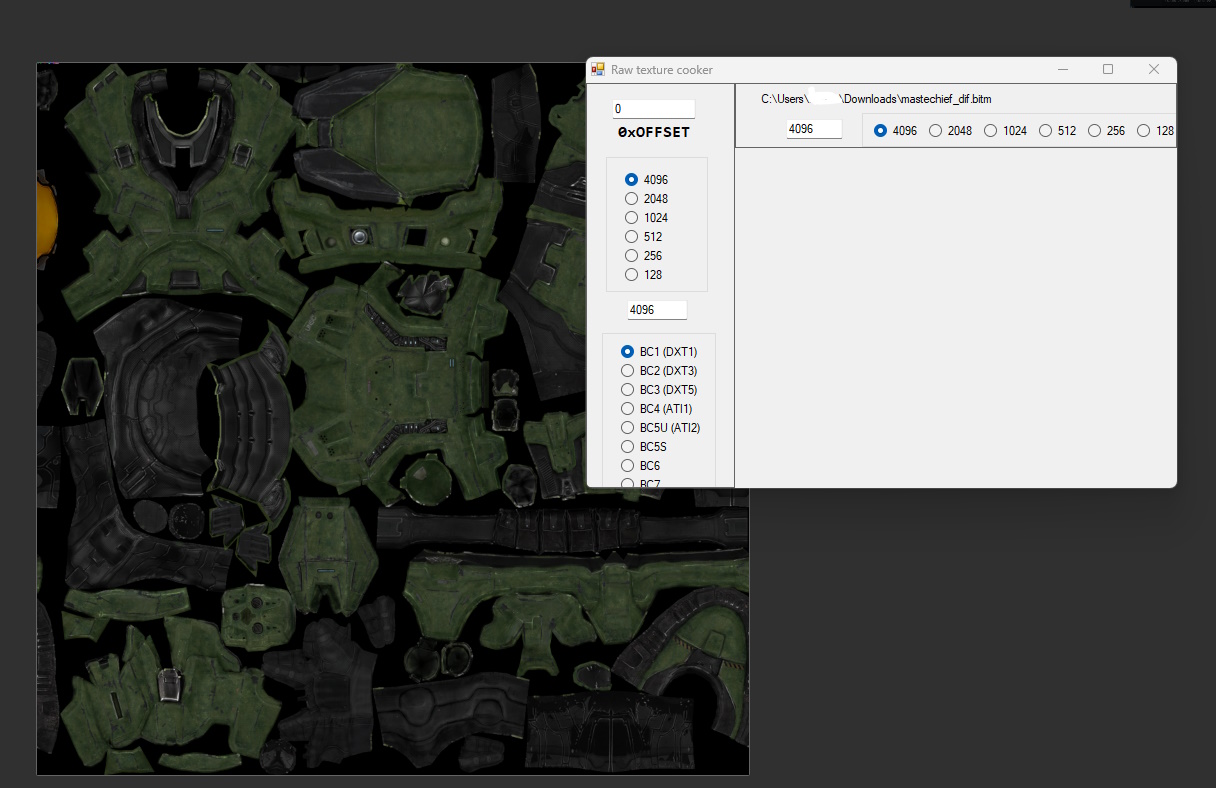

As the first asset in the list seemed to be a bitmap, I extracted the file for masterchief_dif (masterchief diffuse texture) and opened it in ImHex.

What you might notice here is that there seems to be around 272 bytes as a “header”, and you would be correct. Each “asset type” has its own structure and this is the one for a Bitmap image, but I’m yet to figure out it in its entirety. What arguably is more intriguing is the data below, which from my previous experience from other Halo games seemed to be a DXT1 texture file.

After putting it into a very old but useful program called “Raw Image Cooker” and setting the resolution to 4096x4096, I was greeted with this beautiful texture file:

Bingo! We have (almost) fully reverse engineered the main G7 Archive file.

… more on the G7 Engine coming soon!